Electric Curiosities: Home Video Formats

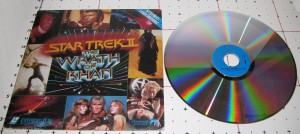

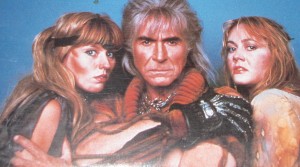

It’s been a while since I’ve done an entry in the Electric Curiosities series, so let me make up for the absence with RICARDO MONTALBAN!

Â ((KHHHHHHHHAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANNNNNNNNNNNNN!!!!))

((KHHHHHHHHAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANNNNNNNNNNNNN!!!!))

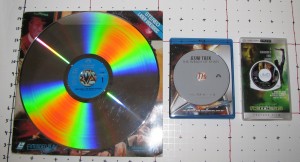

When it comes to watching movies at home, two acronyms jump to mind immediately: DVD and VHS. DVD is morphing into Blu-Ray, and people remember (and laugh at) Beta. If pressed, most people might even mention those “Big CDs”, called Laserdiscs. However, we’ve already forgotten about HD-DVD and no one ever knew about 8mm tapes and CED Video Discs.

Let’s explore some of these various home video formats, shall we?

(And yes, I know this is a departure from the video games I normally talk about, but the name is ELECTRIC Curiosities. Might as well expand the horizons a bit, eh?)

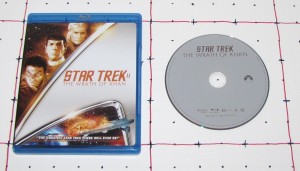

Blu-ray

Blu-ray is the FUTURE. Bigger, better, hi-def, whatever.  I think you all pretty much know what this is, so I’ll save my typing fingers and just move on.

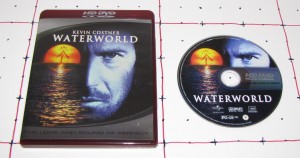

HD-DVD

HD-DVD was a competitor format to Blu-ray. It lost. Oh well. Moving on… ((It failed so miserably, I couldn’t even find any Star Trek releases on the format, other than The Original Series, which would have been unsuitable for this post.))

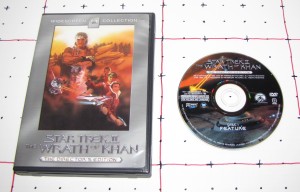

DVD

In the days before DVD, people had to spend hours of their lives painstakingly rewinding video tapes. This was such a horrible experience that stand-alone tape rewinders were available for sale that would do absolutely nothing but rewind tapes faster than VCRs did. You’d get charged a fine at rental shops if you failed to rewind before returning the movie.  Forget about the incredible picture quality improvement, forget about the extra content, forget about multiple soundtracks, forget about instant chapter skips, forget about interactivity: DVD took over because you didn’t have to rewind. No, really, it was that big a deal.

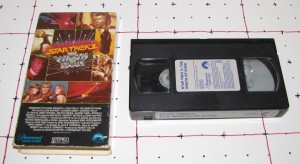

VHS

I couldn’t figure out what in the hell this thing was supposed to be.

It didn’t fit in my XBox. It must be broken. Do I have to break it open or something to get at the movie? I just don’t understand it.

Beta

Before HD-DVD vs. Blu-ray, there was Beta vs. VHS. ((Actually, even after HD-DVD vs. Blu-ray, there’s still Beta vs. VHS, because HD-DVD was such a failure, it couldn’t even beat Beta in the “Biggest Loser Format” competition.)) It had better picture quality than VHS, but lost mainly due to recording time. Initially, Beta did only one hour on a tape. Sony, being arrogant ((See PS3’s $600 launch price tag…)), decided that people would buy it anyway. Then the two hour VHS tape came along. By the time Sony got their act together and increased the recording time, people had already bought VHS VCRs, and because people bought VHS VCRs, rental shops stocked VHS tapes, and because rental shops stocked VHS tapes and not Beta, people bought VHS VCRs. Beta == FAIL. Now, while Beta failed in the home video market, it did quite well in the professional market, such as newscasts. It didn’t really matter that you could only record an hour if you only needed to film fifteen minutes of B-Roll and a five minute interview on location every night. What mattered there was picture quality.  Plus, Beta tapes were notably smaller than VHS tapes, so they were easier to carry around.

8mm

Even smaller than Beta, 8mm tapes were released in the mid-80’s as a competitor to VHS. While they proved to be a popular format for camcorders (because they reduced the size of a camcorder from roughly that of a shoulder-mounted rocket launcher to something that could be used comfortably while handheld), 8mm never really took off as a commercial movie format. It wasn’t any better than VHS quality, and you still had to rewind, what’s more, it cost more than VHS. Commercially sold 8mm movies were largely limited to creepy hotels and airplanes, largely due to their compact size. Also, don’t confuse 8mm video tapes with Super8, which was a film format.Â

Super 8

Don’t confuse this with 8mm video. This is film. A spool of see-through pictures and sprockets. Film.

Super-8 movies came on one or more reels, roughly 15-20 minutes each. The full-length version of The Godfather, for instance, came on 11 reels. This particular film is a “selected scene edition” of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, condensed into a 12 minute run time on a single reel. ((Interestingly enough, this version is the only one that’s actually watchable…)) If you had the right kind of projector, Super-8 movies could have sound, thanks to a magnetic strip on one side of the film. If you had the wrong kind of projector, you had to re-enact the voices, all Rocky Horror style.Â

Laserdisc

Laserdisc was blindingly awesome. Literally. You could use its large shiny surface to reflect the light of the sun into the eyes of anyone who insulted the format. LDs were a foot in diameter, and looked like a record-sized CD. They offered better picture quality than VHS ((And some will say, better than DVD…)) and didn’t have to be rewound. Unfortunately, you couldn’t record to them and they were much more expensive than VHS. On top of that, the makers of the Laserdisc, in order to help prevent deep-vein thrombosis in the audience, decided that the viewer would have to flip or change discs at least once during the film, sometimes as much as three times in a two hour movie, depending on the encoding style. Couch potatoes stuck with VHS, while rich people, exercise freaks, and snobs adopted Laserdisc. Additionally, Laserdisc found popularity in schools, where the clear freeze-frame capability allowed video slide shows with instant random-access scan to a specific frame. Laserdiscs also landed in arcades, where the random access video was used for graphically stunning games like Dragon’s Lair, Space Ace, Time Traveler and Mad Dog McCree. Too bad those all sucked as games.

UMD

So… I really don’t understand UMD. It’s more expensive than DVD. It has a smaller capacity than DVD. It generally has fewer features than DVD. It plays on one thing and only one thing, which nobody bought, and that one thing that has a four inch screen. The library consists mainly of films made between 2000-2005, which no one really wanted to see to begin with. So, uh, why can I walk into Best Buy and still find a UMD movie section? It makes no sense to me at all. It’s like all the stores still have their entire original launch day selection, and they’ve completely forgotten that it’s there. Sony’s even trying to kill the format for games, which is the only reason for it to exist. Why hasn’t it died and gone away? HD-DVD was completely out of stores within about two months of the Blu-ray victory. Why do UMD movies linger so?

VideoCD

A VideoCD contains MPEG compressed video on a standard CD-ROM. It came out in the mid-90’s, around the same time as the first CD based game consoles. Some of them, such as the Philips CD-i and the Amiga CD32, had add-on modules that allowed the console to play VideoCDs. Imagine that, a game console that could play movies. The video on a VideoCD was compressed such that it could be played back in a single speed CD drive. That meant that you could fit about 70-80 minutes of video on a single CD. That, unfortunately, meant that a movie had to come on at least two discs. The quality was generally better than VHS, if you didn’t mind the occasional compression artifacts. Because the video is normal MPEG video, and because the disc is a standard CD-ROM format, PCs have no problem playing VideoCDs. ((Or borrowing the MPEG files for other purposes…)) Also, although you might not be aware of it, there’s a good chance that your DVD player will happily play VideoCDs, since the format is very similar to that of DVDs.

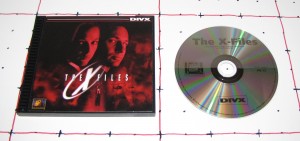

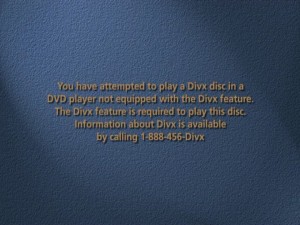

DIVX

DIVX looks like a DVD. DIVX uses the same disc format as DVD. But DIVX is not DVD. ((DIVX is also not related to the Divx codec, except in name, which is a sarcastic reference to this format.)) You see, when you buy a DVD, you get to watch it the night you buy it. You get to watch it the next day. You get to watch it over and over and over until the disc develops stress fractures and disintegrates. That’s the beauty of buying a movie. DIVX didn’t see things that way. The people pushing DIVX (Circuit City and, um… Circuit City) decided that people would want to pay $5 for the disc ((Granted, DVDs were $30+ at the time, so that was a good cheap price.)) and be able to watch it for 48 hours. After that time frame, if you wanted to watch it again, you had to pay again.  Basically, you had to rent movies that you owned. The target market for this was apparently the people who had enough time to go pick up a movie from the store, but who were too busy to be able to take it back to the rental place when they were done and hated late fees. If you wanted, you had the option to pay to upgrade the disc for unlimited viewing. Controlling all of this was a telephone connection to the mothership, where every movie you watched and how often you watched was tracked by the system. And if the mothership didn’t respond, your grand movie collection was worthless.

Yeah… That didn’t work out so well for them. The amazing part is that Circuit City survived for another ten years after this disaster.

You could try to play a DIVX disc in a regular DVD player, but all you’d get is a screen like this:

CED Videodisc

I’ve saved the one that’s probably the most bizarre for last. I’ve given you movies on CD and movies on record-sized CDs, so why not give you movies on a record-sized record? Seriously, the CED ((Capacitance Electronic Disc, if that matters.))  is vinyl and grooved and played back with a contact needle which reads the bumps and dips in a groove. Like a record, the needle would wear out and need replacing over time. Also, like a record, the movies would occassionally skip. There are no known instances of early rappers “Scratching” a Videodisc, but you have to admit that the thought is awesome. ((Actually, though, although you probably could “scratch” a CED, it’s likely that it would simply produce a strange shifting color display as the scanning beam displays the same color for a long time, and, on some TVs, a loss of vertical hold, causing the screen to flip.)) Video quality was roughly on par with VHS, although CED discs could only hold about an hour per side. However, they were initially cheaper than VHS tapes and enjoyed limited popularity among those with lower income or who were just cheap.

While records spun at 33 1/3 RPM, CED discs went at 450 RPM. That means it’s spinning around 7.5 times a second. NTSC Television signals are 60 frames per second ((It’s slightly more complicated than that. NTSC signals typically contain 30 distinct images a second, but each image is shown on two subsequent scans. That’s why NTSC is typically said to be 30 fps, even though it’s really refreshing the screen 60 times a second. Read up on Atari 2600 programming if you really want to gain an appreciation of how TV signals work.)), which means that each rotation showed eight frames. If you look at the closeup of a CED, you can actually SEE the frame spacing.Â

The disc is divided into eight wedge-shaped segments. Each segment is a frame, and the divider is the Vertical Blanking Interval. If you look really closely, you’ll see narrow lines within each segment. Those are individual scanlines separated by the Horizontal Blanking Interval. Think about that for a second: YOU CAN SEE THE MOVIE ON THE DISC. ((Actually, you can see the same thing on a CAV Laserdisc even more clearly. It has to be a CAV disc, though. CLV discs don’t have the same nicely visible alignment. With a CAV Laserdisc, you can see the VBI and HBIs for two frames per rotation.))

CEDs were designed so that they never had to be handled directly, since fingerprints and dirt could screw up the picture or gum up the needle. In fact, CEDs were designed so that you typically never even saw the disc. Movies came in hard plastic caddies. The case was inserted into the player, and when it was removed, the disc stayed behind. An hour later, when you had to flip the movie over, you put the case back in, the disc and plastic ring locked back into place, you pulled the caddy back out, turned it over, then stuck it back in. In order to actually see the disc, you had to unlock the inner ring with screwdriver and pull it out.

Obviously, being vinyl, you couldn’t record on it. But you also couldn’t fast forward, rewind, or pause and still see a picture. The needle made physical contact with the disc. If you fast forwarded or rewound, the needle had to be lifted in order to prevent damage, since the action was done not by speeding up the disc, but by moving the needle in or out, just like going to the third song on an ordinary record. As for pausing, the needle also had to be lifted. The disc was one continuous groove. If you left the needle on the disc, it would track with the groove, so it would play the movie. If you held the needle in place and prevented it from tracking, it would have to jump the groove wall, probably damaging both the needle and the disc. At the time, the electronics required for keeping a frame in some kind of memory so that the video could be paused and still show an image were insanely expensive. ((VHS/Beta did it by simply rescanning the same frame over and over. Most Laserdisc players only had a pause feature on the CAV style discs, because the physical layout of the frames on the disc allowed the laser to remain stationary and simply scan the same frame over and over and over. CLV discs couldn’t be paused because of the variable frame alignment.))

One of the most interesting tidbits about the Video Disc is the fact that there were plans to produce an add-on for the ColecoVision which could drive a CED player for games. Imagine how that could have changed EVERYTHING about the video game industry. Affordable, random access, full motion video games in your living room, in 1983. Sure, there would have been a lot of Mad Dog McCrap, but I have one word for you: Myst. In 1983. It wouldn’t have been a computer-generated photo-realistic world, but there would have been games that were just as immersive and beautiful. We would have had the CD-ROM revolution ten years earlier. In that world, would Super Mario Bros. even have existed? How could low-res blocky 16 color graphics compete?

That concludes the tour for today. For scale comparison, here’s a couple of shots with the different formats, all happily coexisting.

So now, before you go and pirate a movie off the IntarWebZ, think for a minute about what you’re missing. Sure, you may be able to get a shiny HD copy of the latest movie in a matter of minutes with just a few clicks, but you don’t get a badass three inch tall picture of Ricardo Montalban on the case!

Â ((KHHHHHHHHAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANNNNNNNNNNNNN!!!!))

((KHHHHHHHHAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANNNNNNNNNNNNN!!!!))

February 18, 2010 No Comments

James Cameron Plays Too Many Video Games

Let’s see…Â He’s played…

Final Fantasy X:Â

Â

Suteki Na De cutscene

Â

Panzer Dragoon Orta:

Â

Episode 2: Altered Genos

Episode 4: Gigantic Fleet

Secret of Mana:

Â

Title Sequence ((The Japanese version because it shows more of the tree.))

Â

Mana Tree Cutscene

Â

Command & Conquer:

Mechanical Man

The Orca

Â

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time

HEY! Listen!

January 3, 2010 No Comments

Tidbits

I seem to have been neglecting this lately. I’m a week overdue on a programming/testing post, and it’s almost getting to the point where I’m late on a video game history lesson. So, to prove I’m not dead, here’s a few bits of here and there.

First, if you’re in Washington, you have less than a week left to Approve Refererendum 71. I already have. Have you?

Now, back to games and things. Here’s a few of my latest acquisitions.

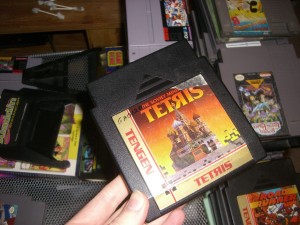

This one should require no introduction or explanation. Tengen Tetris. I spoke about this game several times in previous entries, alluding to the legal fight between Atari and Nintendo, but always in passing. Now that I actually have a copy, I’ll have to devote an entire article about it. That’ll be in the future, but for now, to illustrate its awesomeness: Two-Player Cooperative Mode.

The second notable acquisition is a Japanese Famicom game called Metafight. Well, it’s actually “Something-Something Metafight”, but I don’t know Japanese. The cover has some generic anime characters, one of which looks angry. None of that really matters. I’m not really into Japanese things and I’m not really into anime or stuff like that. And I don’t have a Famicom system.  So, then, you ask, why would I go out of my way to buy a Japanese anime game for the Famicom?

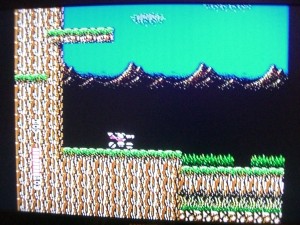

This screenshot might help you figure it out. It at least might look a bit familiar to you. Maybe. Can’t quite place it? This’ll do it:

Metafight is the Japanese version of Blaster Master. ((And if you don’t know what Blaster Master is, well, you just need to play more NES games.)) There is no opening story sequence in Metafight, which automatically means that the plot for Metafight makes far, far more sense than the “My pet frog jumped on a box of radioactive waste in my backyard and went down a hole and I followed it and found this bad-ass hyper-agile tank in the underworld and I proceeded to fight lots of nasty creatures in my bad-ass hyper-agile tank in order to rescue my radioactive mutant pet frog and save the world from the radioactive mutants that live under the Earth’s crust” plot that Blaster Master tried to have. Of course, since Blaster Master changed the story from whatever angry anime guy was doing to something stupid about a mutated frog, they had to change the tank ignition sequence to be in a cave, instead of Metafight’s futuristic tank garage.

But enough about that for today. It’s time for robots.

It’s been a while since I’ve visited the land of the video game playing robots, but I assure you, I have been thinking about them. I think the next time I get back into them, assuming I ever do, the first thing I’ll do is organize the codebase. It was built to get it to market, but not built for future expansion. If I want to keep going with this, I’ll need to rewrite large sections of it and separate the movement interface and screen capture plumbing from the game specific recognition and logic code. Although it won’t be quick, that should hopefully be reasonably straightforward to do. From there, I’d like to work on improving the control of the paddle. A few weeks ago, I think I may have improved the precision of the controls, but I still haven’t tested it out.

At any rate, I think Pong is the wrong game to try to develop precision controls. The trajectory projection gets in the way of making sure the paddle is moving exactly where I want it to go as fast as I can get it there. The paddle might very well be going where I want it, but by the time it gets there, that’s no longer where I want it. So, I think I’m going to have to try another game to tune the paddle controls. Right now, I’m leaning toward Kaboom! as the game of choice. It should have easy to program recognition and logic (Bomb drops straight down, move to catch bomb, repeat), and it will absolutely require precision, accuracy, and speed. Runner up is Indy 500, but I think the pathfinding and collision avoidance knock that one out at this point, not to mention the 360 degree driving paddle. An interesting side-note is that pretty much whatever paddle game I choose, I’ll have to deal with something I didn’t care about in Pong: The button.

Beyond the paddle, to really get things done on the Atari 2600, I’m going to need to be able to control a joystick. I have several options, of course. I can try some alternative controller, like the button operated Starplex or the gravity operated LeStick, but really, or maybe try to build my own controller, but really, to claim that I built a robot that can play an Atari 2600, I have to build something to handle a good old CX40 Atari Joystick. That’s probably not going to be easy. The controls won’t have to be as precise as the paddle, since there’s only nine options, however, it’s going to involve control on two axes that are somewhat dependent on one another. I’ve had thoughts involving double arms that push or pull, a swing arm with a piston, a gantry crane like setup, and something that rotates and can push the stick, and none of those ideas seem any good at all. I’m sure I’ll think of something.

October 27, 2009 1 Comment

Electric Curiosities: Pac-Man vs. K.C. Munchkin

The game is familiar. You play a round creature that lives in a maze. You’re chased by monsters and have to eat dots to survive. Some of the dots let you attack the monsters temporarily. When you get all the dots, the maze resets at a higher speed. It’s a lot like Pac-Man, but it isn’t. The game is K.C. Munchkin, and you’ve probably never heard of it, let alone played it.

If you have heard of K.C. Munchkin, then it’s probably because of the lawsuit.

Back in the early 80s, a widespread and highly contagious disease known as “Pac-Man Fever” infected millions of people around the world. The only known cure for this pandemic was to eat lots of dots, power pellets, and ghosts in your local restaurant, bar, convenience store, or darkened rooms where people repeatedly paid good money to stand in front of a TV for five minutes, known as “arcades”. ((Sadly, arcades are now thought to be extinct in the wild. The last non-captive arcade died in late 1994, in Burlington, WA, when it was eaten by a Seattle’s Best Coffee.)) Eager to help fight the spread of this horrifying condition, Atari, who was the leading video game manufacturer at the time decided to help sufferers of Pac-Man Fever get their treatment in the convenience of their own home, and purchased the exclusive rights to develop and distribute a home version of the cure.

Obviously, this was a big deal for Atari, who was starting to get a bit of competition in the home console market. Most of it was weak and incapable of causing any harm, but some of it, like the Intellivision, constituted a clear and present danger. By grabbing the license to the biggest video game in the history of video games ((Which, of course, was only about ten years at the time…)), they grabbed a license to print money. Not only would the Atari 2600 have a sure-fire hit, their under development Atari 5200 console would have a sure-fire hit, their computer line would have a sure-fire hit, and, on top of that, the Intellivision would have a sure-fire hit, because Atari put profits before console exclusivity. To summarize, Pac-Man == $$$.

Naturally, mega hits will spawn imitators. Magnavox, the makers of the Odyssey2 system, which was one of the legitimate competitors to Atari ((And by “legitimate competitor”, I mean that it had measurable market share, a decent library of games, and had survived for more than a year. You may not have heard of this console, but it did exist. Honest.)) decided to produce a Pac-Man imitator. However, since it was clear that a straight Pac-Man ripoff would get them sued, they made some changes to the game play. Keep the maze, but make change. Keep the big round chomping critter, but make it blue and give it antennae and a smile. Keep the creatures that chase you, but only include three of them and make them look like aliens. Keep the dots and power pellets, but have far fewer of them, and, most importantly, make them move. Throw in multiple mazes, invisible mazes, and a maze editor.

And one more thing, release it first.

Here is a leaked photograph of Atari executives at the very moment that they heard about K.C. Munchkin:

Pac-Man == $$$. Threat To $$$ == Lawyers.

Atari sued to halt distribution, claiming copyright infringement. K.C. Munchkin was clearly inspired by Pac-Man, and the differences clearly show that Magnavox knew that they were stealing. Atari lost. Although there were similarities, the court reasoned, there was nothing directly stolen and any reasonable person looking at both works could easily tell that they were different.

But remember, Pac-Man == $$$. Threat To $$$ == Lawyers.

Yep, Atari didn’t go down that easily. They appealed and this time, they won. K.C. Munchkin was pulled from the shelves, Atari was free to make millions from the distribution of home versions of Pac-Man, and Atari, Inc. v. North American Philips Consumer Elecs. Corp. entered into court precedents.

The thing I don’t understand about all this is how this lawsuit didn’t completely devestate the video game market permanently. As I’ll talk about, K.C. Munchkin is clearly not Pac-Man, but it is clearly Pac-Man like. But the same holds true for many games. The industry is founded on imitation. Sonic stole from Mario and Mario stole from Pitfall. Gradius is Space Invaders moving forward. There are hundreds of Doom clones and GTA clones. And I can’t even tell the difference between Guitar Hero and Rock Band. All of these knock-offs should have been destroyed by the precedent set by the lawsuit, but it never seems to get used. In fact, I don’t think Magnavox was sued for their Breakout clones Blockout/Breakdown or their Space Invaders clone Alien Invaders – Plus! ((Where Plus == Suck)) or their Outlaw clone Showdown in 2100 AD or their Street Racer clone Speedway or their Indy 500 clone Spin-Out or… The list can go on. Why, then, was K.C. Munchkin singled out for the attack?

Jealousy.

Magnavox did it first, and, more importantly, Magnavox did it better. ((See also the lockout chip lawsuit that Nintendo filed against Tengen/Atari when Tengen released a better version of Tetris than the Nintendo one…)) The existence of K.C. Munchkin was an embarassment to Atari. It was not a real threat to Atari. Atari was guaranteed to make bucketloads of money with the Pac-Man license, and K.C. Munchkin on its own wouldn’t have put a dent in it. However, because Atari was guaranteed to make bucketloads of money with Pac-Man, they wanted it fast, they didn’t care about getting it right. I’m not going to say that Pac-Man for the Atari 2600 was an unmitigated disaster of a game, because it’s not. As far as Atari games go, it’s not that bad. Where it fails is in the comparison to the arcade version. It’s blocky, the ghosts are all the same color and they flicker, the colors are all wrong, the sound is horrible, the maze is different, there’s a weird rectangle instead of fruit. It’s like ordering a reproduction of the Mona Lisa and getting a crayon drawing from a six year old instead. It’s just disappointing. So to have K.C. Munchkin laughing from the sidelines, where a third-rate competitor one upped the official licensee, with its multi-colored non-flickering enemies, its decent sound and its sharper graphics, that was intolerable. If the Atari 2600 of Pac-Man version had been a closer replica of the arcade game and had it come out first, Atari probably would have left K.C. alone and that game wouldn’t be remembered for anything today.

So, then, let’s take a look at the legendary K.C. Munchkin for the Magnavox Odyssey2 and how it compares to the infamous Pac-Man for the Atari 2600.

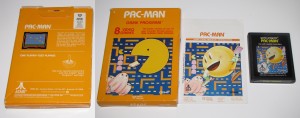

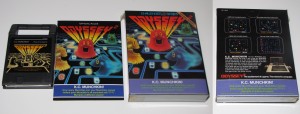

Straight away, it’s clear that KC Munchkin is not Pac-Man. You would not have seen this game in a store and mistakenly believed that you were buying Pac-Man. From the front, it’s hard to even tell that the game is Pac-Man like. I do have to give KC Munchkin (And Odyssey2 games in general) bonus points for their box art, which always looks like it should be painted on velvet and viewed under a black light. Bizarre smiling shaggy things and glowing cubes, and the wooshing Odyssey2 logo ruling over all.

Pac-Man, on the other hand, just looks like the game. It’s really boring, by Atari standards. Usually the box art is so fanciful and wild that it barely resembles anything remotely related to the game inside, but for Pac-Man, it looks like the game. Even worse, it looks like the Atari 2600 version of the game, not like the arcade version. Consumers should have known what they were in for when they saw it. Somewhat mysteriously, the large Pac-Man figure on the outside of the box looks nothing like the cartoony Pac-Man that’s on the cartridge itself. I don’t know of any other Atari game where the box art is different from the label art like that.

As far as the back of the boxes go, KC promises multiple mazes, invisible challenge mazes, and a maze editor. Pac-Man promises … a children’s mode.

While KC Munchkin wins on the packaging, Pac-Man wins on the instruction manual front. Inside the Pac-Man manual are detailed and whimsical drawings of the characters and items in the game. Inside KC Munchkin’s official rules book is difficult to read white text on a black background, surrounded by game sprites and random numbers and letters, some of which have inexplicable Superman trails. I think the glowing question mark sums up the KC Munchkin instruction book.

The Pac-Man playfield just looks sickly. Blue and kinda sickly yellow. Really?  The arcade game was blue walls on a back background. The Atari is capable of producing the colors blue and black. So why the change? Even Pac-Man looks queasy in that environment. K.C. Munchkin, however, has bold purple walls on a black background. Easy to see, and look how happy KC is as he ((He? I don’t know. I suspect that KC is pulling a Samus on us.)) strolls around the maze. The Pac-Man maze is a symmetrical, rectangular affair, without the twists and turns of the original. KC lives in an asymmetrical tangle of passageways, forcing you to develop different strategies for the left or the right of the board.

If you look at the Pac-Man shot, you’ll see that there are only two ghosts and only two power pills. That’s because the ghosts and power pills flicker like mad because the Atari has limited sprite capabilities. The programmer actually only displayed one ghost every frame, and it just looked like four because the other ghosts hadn’t faded from the CRT yet. They’re all the same color because he was lazy.  Unfortunately, the all digital PC input device I’m using captures frames as they are. I recorded at 30 FPS, which means that I got two frames of the Atari screen, therefore two ghosts. There really are four ghosts and four pills. For the KC shot, what you see is really what’s there. Three creatures, each of a different color, and four special munchies. The special munchies will flash to an X every once in a while, so you can easily tell what they are, but that’s the only flickering you’ll get in this game.

The KC characters are more detailed. They have more visible features and have distinct up and down animations, as well as left/right. Pac-Man is always in profile and the ghosts never look like they’re moving in any particular direction.

And then there’s the dots. The dots are really what makes K.C. Munchkin stand out. Most Pac-Man based games are full of dots. They’re everywhere, and you have to go everywhere to get them. Not so in K.C. Munchkin. In this game, there are only twelve dots. Four power dots and eight regular dots. The catch? The dots move. That one little feature is what makes K.C. Munchkin be powered by awesome. Not only do you have to run away from the monsters, you have to chase down the dots. At first, they’re lethargic, but as you eat their brothers and sisters, they become less complacent and more alert, until the last remaining dot is hauling ass at the same speed you move through the maze. You have to plan ahead to cut it off, while at the same time, you have to make sure you’re not being drawn into an ambush by the three critters.

Another major difference in the gameplay of KC Munchkin is that you only get one life. It’s a theme that runs through many Odyssey2 games ((Probably unsurprisingly, since half of them were written by one guy.)). One life, no bonus lives. Your score is only as good as your best run. Make one mistake, and you’re back at zero. It’s a bit disconcerting at first, but it ends up working to the advantage of the game. Your near death scrapes with the red critter as you hunt down that last dot are made much more tense and exciting by the fact that you don’t get to try again.

Pac-Man Audio | K.C. Munchkin! Audio

And finally, the sound. Pac-Man is about as pleasant to listen to as a trash compactor. Every dot you eat sounds like an electric banjo being massacred, the death sound and start game sound are just grating. Only the power pellet and eating ghost effects are remotely pleasant to listen to. None of them sound anywhere remotely like the arcade sound effects. The programmer didn’t even try. K.C. Munchkin has a considerably mellower sound. It’s still early home console sound, so it’s not all that great, but it won’t have you reaching for the mute button and a pack of earplugs to block out the horror while you play.

Of course, all that text and all those pictures don’t really mean much. You have to see the games in action to truly compare them.

What came next? Well, Pac-Man obviously continued on his path of fame and fortune and is still making games today. On the Atari 2600 front, Ms. Pac-Man was released a few years later and was simply awesome, fixing pretty much everything that went wrong with the original. Fame, however, was not in store for K.C. Munchkin. He starred in one other game, called “K.C.’s Krazy Chase”, which was a semi-autobiographical depiction of his legal battles. Afterward, he retired from the video game scene, and is now a veterinarian in Upstate New York.

Bottom Line: If you’re a hard-core dot munching Pac-Fan or if you are considering buying an Odyssey2 system for your collection, you need to get a copy of K.C. Munchkin. If you already have an Odyssey2 system and don’t have this game, there is something wrong with you. If you’re a more casual fan, not willing to drop $100 on a 30 year old console just to play this one game, then there might be emulators or Flash versions available. I’ve never bothered to look, since I have the real thing.

October 18, 2009 2 Comments

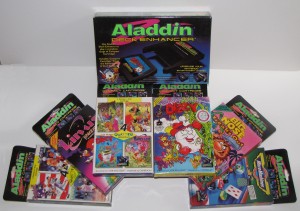

Electric Curiosities: The Value of Plastic

Last week, I wrote about the Aladdin Deck Enhancer. I was prompted to write about it because I had recently acquired one from a popular on-line auction site that is a primary enabler of my addiction. It was the complete set, the main unit and all six games that were released. On top of that, it was sealed. In a stroke of luck, I paid $70 for the lot. However, since it was a complete set, in very good condition and sealed, it was probably worth about $200-300. In fact, just the bare unit and all seven loose cartridges would potentially be worth $70 all by itself.

In video game collecting, as in many other types of collecting, the sealed package demands a premium. For instance, a complete copy of Super Metroid can run you $40-50, but if it’s still factory sealed, you’re looking at a minimum of $400. A used copy of Sgt. Pepper on Vinyl might sell for $10, but with an unbroken covering of the original plastic, you might have to talk to Christie’s Auction House.

Thing is, I don’t see the point.

With a quick little slice, I “lost” at least $150 on that Aladdin Deck Enhancer, and it doesn’t really bother me. ((Although, I did consider trying to find someone who had an opened copy and would be willing to trade for a sealed copy. After all, it might not be worth anything to be, but I know that someone out there might want it.)) In all honesty, what good is a bunch of games to me if I can’t play them? If it’s sealed, it might as well be a pretty box with rocks inside. While I like the container, it’s what’s contained that I really care about. I have to wonder how many other collectors out there feel the same way.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m not about to do something insane like break the seal on a copy of Chrono Trigger. Instead, I just avoid buying anything that’s still wrapped in unbroken plastic, unless the price is such that I won’t lose any sleep over it. It’s no great loss to the Video Game World that an Aladdin Deck Enhancer has been unwrapped. It’s probably still worth more than I paid, even with the plastic opened.

October 7, 2009 No Comments

Electric Curosities: Enhance your NES!

Back in the early 90’s, toward the end of the life of the NES, the company who was responsible for the Game Genie came up with another idea to make Nintendo angry. It was called the Aladdin Deck Enhancer. Reportedly designed to allow “enhanced” games on the NES by providing extra RAM and better graphics, it was called “the future of console game play” by its very own box. In reality, however, it was an ill-timed plot to sell cheap, unlicensed games for the NES.

Cartridges for the NES were fairly expensive to produce. It wasn’t just the ROM chip, a simple circuit board, and a big plastic shell, like there was in the days of the Atari. Sometimes NES games needed some extra memory, sometimes they needed a graphics coprocessor, but they always, every single one of them, needed the additional electronics to satisfy the 10NES lockout chip.

You see, Nintendo learned a lesson from the Great Crash of 83. Atari didn’t have any kind of lockout device on the Atari 2600. This allowed third party developers like Activision and Imagic to produce some of the best titles of the system without needing the permission of nor needing to pay Atari. It also allowed anyone with a ROM burner to produce mountains and mountains of unashamed garbage that masqueraded as video games. You think ET caused the Crash? No. Custer’s Revenge caused the Crash. Star Fox caused the Crash. ((Not THE Star Fox, although, interestingly enough, Star Fox for the Atari 2600 is the reason THE Star Fox had to be called “Starwing” and “Lylat Wars” in Europe. ))  Nintendo wasn’t going to let their system be killed by crappy games. The solution to this problem came in the form of the 10NES lockout.

By setting up a two-part lock electronic lock, they prevented a critical mass of lousy games from accumulating and thereby averted a full scale market implosion. ((Atari learned the same lesson. In its 7800 ProSystem console, there’s a lockout mechanism that’s so strong that it is actually against the law to export an Atari 7800 due to restrictions governing military grade cryptography. In Atari’s case, however, a second full scale market implosion was avoided, not by the lockout chip, but rather by not actually having a market that could implode.)) One part was in the console. When you put in a cartridge and turned the power on, a challenge was sent to the cartridge. If the cartridge responded properly, then you got to play the game. If the cartridge failed to respond correctly, you got a blinking power light and a flashing gray screen of death. And the only place to get the chip that acted like the key to the lock was Nintendo. They patented and copyrighted the design, so they’d sue you no matter what you tried to do to circumvent the lockout. But, Nintendo also recognized that the key to a successful console was third party support. Game publishers were welcome to make games for the NES, as long as they abided by all sorts of requirements and rules (Including censorship), and, on top of that, pay for the privilege of getting the chip for the cartridge and the “Nintendo Seal of Quality” on the box.

The program was successful. Because of it, Nintendo avoided a flood of terrible and worthless games. Sure, there were games that sucked, but for the most part, anything that had the Nintendo Seal of Quality was at least half-way decent.  Even crap-buckets like Total Recall or Super Pitfall were miles above the uninspired and derivative silicon wastelands that plagued the Atari 2600 in 1983.   The lockout chip also made piracy of NES carts more difficult. Without the 10NES key chip, a game wouldn’t play, and Nintendo wasn’t about to hand out those chips to pirates.

Of course, the flip side should be obvious. Because Nintendo controlled the chip that was the key to the system, Nintendo controlled every game that was allowed to play on it. Want to put out a game with blood in it? Nope. Want a game with strong religious themes or symbols? Ain’t gonna happen. Adult content or mature themes? Uh-uh. Want to release the same game for the NES and for Sega? Not for another couple of years. Want to put out more than a handful of games a year? Fat chance.

Don’t want to pay the licensing fee to Nintendo…?

Whenever there is a technology that will prevent someone from making money, that someone will find a way to defeat that technology, thereby allowing money to be made. That is exactly what happened with the 10NES lockout chip. Some people created pass-through carts, which looked like a Game Genie and required you to plug in a licensed NES cartridge in order to play. It then used the real 10NES chip in the licensed cartridge to unlock the NES, which then loaded the unlicensed game in the passthrough. Other companies thought that was too tacky looking and instead decided to simply fry the 10NES chip in the NES system by sending it a voltage spike. However, the truly dedicated ones reverse engineered the 10NES chip from the specifications in documents obtained under false pretenses from the US Patent Office. The corporation who was responsible for this awesome act of technological trickery? Atari. The Atari who had been nearly destroyed by unlicensed games had decided to create its own unlicensed NES games under the Tengen brand, largely to get around Nintendo’s licensing fees and severe non-compete restrictions. ((And, of course, they got sued… Although some may claim that the lawsuit was less about protecting their technology than protecting their reputation, as the lawsuit focused on the Tengen version of Tetris, generally considered superior to the Nintendo version. (Much the same way that Atari had sued Magnavox for the superior K.C. Munchkin infringing on the less-than-stellar 2600 Pac-Man…) ))

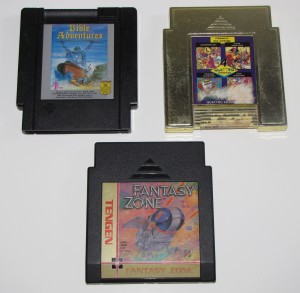

Unlicensed NES Cartridges: Bible Adventures (Wisdom Tree), Quattro Adventure (Camerica), Fantasy Zone (Tengen)

Most manufacturers of unlicensed NES games ended up following in Atari/Tengen’s shoes and created 10NES knock-off chips. However, those chips raised the cost of producing a cartridge and cut into the profit margin. Which brings us back to the Aladdin Deck Enhancer that I was talking about before I went off on that long-winded tangent of a history lesson. You see, there was nothing about the Aladdin Deck Enhancer that was really an enhancement at all.  It actually wasn’t about the extra memory, it actually wasn’t about the graphics coprocessor. It was about the knock-off 10NES chip. The plan behind the Aladdin Deck Enhancer was that they’d sell the base cartridge, which contained the lockout chip and some other chips, then sell the games that plugged into the base separately. As many games as you wanted, but only one lockout chip. The games, since they wouldn’t need to include the extra electronics, would be cheaper to produce and therefore cheaper to sell. On top of that, why not license other games for use with the Aladdin Deck Enhancer? Certainly there are other companies or game developers itching to get their games on the NES without having to deal with the Iron Fist of the Big N. It’s like a license to print money!

Or rather, in 1988, it would have been a license to print money. But the Aladdin Deck Enhancer came out in 1993, firmly in the period of 16-bit domination. If people wanted enhanced graphics and bigger games, they didn’t buy games on some convoluted half cartridge that required some bizarre mutant shell for them to work. No, they went out and bought a Super Nintendo. The company which distributed the Aladdin Deck Enhancer was ruined and folded a few months later.

The game “Dizzy The Adventurer” was included as a pack-in cartridge. The other six cartridges released were The Fantastic Adventures of Dizzy, Quattro Adventure (including Boomerang Kid, Super Robin Hood, Linus Spacehead, and Treasure Island Dizzy ((It’s obvious that Codemasters felt that Dizzy would be their killer app, with three Dizzy games available for the unit and another one promised on the box. Although apparently big in the UK, sadly, the failure of unit meant that Prince Dizzy of the Yolk Folk would remain obscure in the US…)) ), Big Nose Freaks Out, Micro Machines, Quattro Sports (including Baseball Pros, Soccer Simulator, Pro Tennis, and BMX Simulator), and Linus Spacehead’s Cosmic Crusade. ((If you’re ever in need of a Commodore 64 flashback, you should give Dizzy or the games on Quattro Adventure a spin. Not that you ever actually played those games on a C64, but they’ll certainly remind you of one.)) 11 other games were promised on the box, and while none of those were released as Deck Enhancer carts, most were later (or had already been) released as standalone unlicensed NES carts. While not crowning pinnacles of gaming glory, the Aladdin games aren’t complete abuses of the physical properties of silicon.  It’s likely that some of the games would have easily been qualified for the “Nintendo Seal of Approval”, had they wished to go legit. ((And if they hadn’t been made by the same people who made the Game Genie…))

October 3, 2009 2 Comments

Electric Curiosities: The Lost Art of Cartridge Design

These days, with the exception of the Nintendo DS, video games come on boring shiny discs that look pretty much exactly the same as every other game for every other competitor’s system. You can’t tell the difference between the games for two consoles by feel alone.

It was not always like this. Deep in the mists of time, video games all came in chunks of plastic called “Cartridges”. By look and feel, you could distinguish one system’s games from another’s. Sometimes cartridges for a system were plain and rectangular, sometimes they were embellished with features like handles, and sometimes they were yellow… Bright yellow. This post explores the cartridges for a number of different systems, some of which may be familiar to you, and some of which will hopefully strike you as freakish and bizarre.

First off, the full gallery, for size comparison. For fun, I’d recommend trying to see how many of these cartridges you can identify without zooming in all the way and reading their logos.

If you don’t recognize at least three, you’re probably not going to find the rest of this post very interesting. And if you can name all of them, then feel free to start naming cartridge-based systems that aren’t represented here. There are still a few systems that I haven’t raided eBay for yet…

Anyway, without further babbling, the carts:

Atari 400

(Pictured: Centipede)

The Atari 400 computer had a small (by Atari standards) cartridge with a plain text brown label. The cart contacts were protected by a sliding door, which was partially exposed, unlike the doors on 2600 and 5200 carts. The Atari 800 had two cartridge slots (because one is never enough), but the slots were not equivalent, forcing Atari 400/800 games to have a marking on the top of the cart telling you to insert it into the left or the right cartridge port. However, since people didn’t buy the Atari 800, not many cartridges were made for the exclusive right port, leaving it lonely and depressed. ((It later found love in the form of the similarly ignored NES expansion port.))

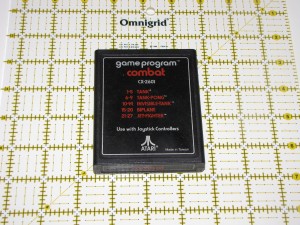

Atari 2600

(Pictured: Combat)

According to what trusted sellers on eBay have told me, this is Combat for the Atari 2600, which is apparently EXTREMELY RARE (LQQK!). I had never heard of this game or this system before, so I don’t have much information on it to share.

Atari 5200

(Pictured: Robotron 2084)

After their apparent disastrous failure with the Atari 2600, Atari bounced back and produced the Atari 5200, which, as the name implies, was twice as good as the 2600. 5200 carts were the largest Atari carts, with the height of a 2600 cartridge, but the width of a SNES cartridge. Typical 5200 carts were silver labels, with an image on the label and blue Atari branding. Unlike the multiple rebrands of Atari 2600 cartridges, the 5200 did not survive long enough to change this basic design.

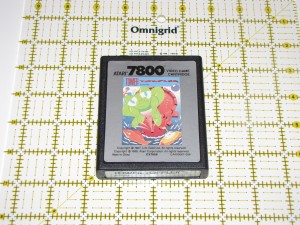

Atari 7800

(Pictured: Tower Toppler) ((Also known as Nebulus or Castelian))

During the rise of the NES, Atari released the 7800 ProSystem. Learning from some of the mistakes they made with the 5200, the 7800 had 2600 compatibility, which lead to the 7800 using a size and shape identical to the 2600 for its cartridges. 7800 carts mostly had a silver border and plain text end label, with game art in the middle of the main label.

Atari Jaguar

(Pictured: Iron Soldier)

The last gasp of the once powerful Atari, the Jaguar came out right at the transition between 2D and 3D and would have had more success had most of its games not completely sucked. (I’m looking at you, Checkered Flag. And Club Drive.) The cartridges used the extremely popular 2.75 x 4 form factor (Similar to the size used by the Genesis, SMS, Famicom, N64, TRS-80, TI-99, and Tomy Tutor), but for some inexplicable reason, had a tube shaped handle on the top.

Atari Lynx

(Pictured: Scrapyard Dog)

Lynx games are some of the flattest in this set, about two credit cards thick. The contacts are exposed directly beneath the label. Most Lynx games had a curved lip at the top edge, allowing you to pull the game out of the system after it’s inserted. The Lynx is one of the few systems in this set where you can’t see what game is in the system after you’ve put the cart in, as the label faces the back of the system, instead of outward like on the Game Boy.

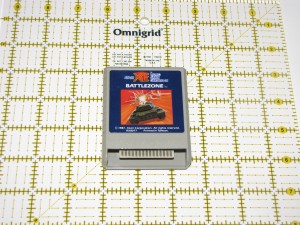

Atari XE

(Pictured: Battlezone)

The Atari XE Game System was Atari’s competitor to the Atari 7800. The two systems fought each other valiantly and both were slain in the process. The XE was compatible with Atari 400/800 series games, so XE carts were the same size and shape. The color was changed because by the late 80’s, people had realized that the early 80’s were ugly. The label was updated to include game art. And finally, the bizarre half-exposed dust door on the 400’s carts was removed for the XE.

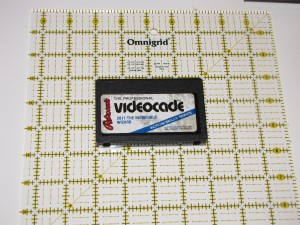

Bally Videocade

(Pictured: The Incredible Wizard)

Bally Astrocade/Videocade/Professional Arcade ((No one seems to actually know what this thing was called, not even the system itself.)) had cartridges that wanted to be cassette tapes. While they didn’t have winding spools or magnetic tape, they did have what appears to be write-protect tabs that were punched out. These holes were used to hold the cartridge in place after you inserted it, because Astrovision Videocade ((or whatever)) cartridges possessed limited intelligence and were known to try to escape when you turned the system on.

ColecoVision

(Pictured: Donkey Kong)

The ColecoVision knew a good thing when it saw it. Why try to come up with your own cartridge design when you can steal the one that was Atari was using?  Coleco carts are the same size and shape as Atari 2600 cartridges, but had controller overlay slots in the back and the label was reversed so that you’d see it the right way up when it was in the system. Oh, and there were little ridgey things at the top, and the case was slightly beveled to prevent you from trying to jam a Coleco cart in an Atari or an Atari cart into a ColecoVision. This cartridge camouflage is especially useful now, as less savvy eBay sellers can’t tell the difference between an Atari 2600 cartridge and a generally more valuable ColecoVision cartridge, allowing someone who can tell the difference to take advantage of them. Unfortunately, the label design for a Coleco game kinda sucks, giving the ColecoVision name more prominence than the cartridge title, and limiting the custom artwork to the title itself. ((And when they were selling the Adam computer, the corporate labeling read “ColecoVision & ADAM”, making it even larger and even more obnoxious.))

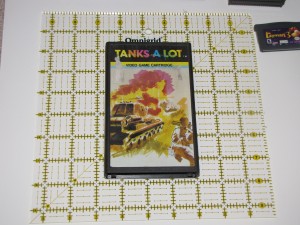

Emerson Arcadia 2001

(Pictured: Tanks A Lot)

The Emerson Arcadia 2001 wasn’t satisfied with the 3×4 cartridge that the Atari and Coleco had. Oh no, they had to push it to the max. As a result, the Arcadia carts are 6 FULL INCHES of rainbow-titled watercolor AWESOME. And why stop there? Why not put a label on the BACK side of the cartridge, too?

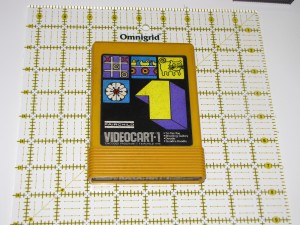

Fairchild Channel F

(Pictured: Videocart 1: Tic-Tac-Toe/Shooting Gallery/Doodle/QuadraDoodle)

They’re yellow. They’re big. And they’ve got giant psychedelic numbers on them.

Nintendo Game Boy

(Pictured: Kirby’s Dream Land)

Game Boy cartridges are about the smallest a cartridge can get without feeling too small. It’s large enough that you can’t eat it and won’t permanently lose it in the seat cushions, but small enough to take large quantities with you wherever you go. It’s got a big spot for label art that isn’t invaded by branding, since the branding is built into the cart itself. These carts must have evolved from stray Bally carts, as they also have a notch for a locking device to prevent their escape. It’s also one of the few carts that tells you how to put it in the system, with a large arrow in the plastic and the words “THIS SIDE OUT” on the label.

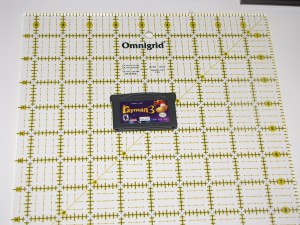

Game Boy Advance

(Pictured: Rayman 3)

The GBA cartridge was about half the height of a Game Boy cart, leaving less room for artwork on the label. The system branding is still on the plastic and the insertion arrow is still there, but the label no longer tells you which direction faces out, leading to mass customer confusion.

Game Boy Color

(Pictured: Blaster Master Enemy Below and The Legend of Zelda Oracle of Seasons)

The Game Boy Color cheats in its quest to gain attention by having two types of cartridge that I have to comment on. There’s the Black Mutant Hybrid cartridges, which are identical to standard Game Boy carts, only black. These mutated black cartridges could be played on an ordinary Game Boy, but also contained Game Boy Colorized versions of the games. Then there’s the similarly sized clear carts, which are strictly for the Game Boy Color. The system branding region that had been indented on regular Game Boy carts was inverted into a bubble on the clear carts. Additionally, by the release of the GBC, the clear carts had been sufficiently tamed and no longer attempted to flee when they were played, so there was no need for a locking mechanism on the system, which means that they do not have a notch in one of the corners.

Intellivision

(Pictured: Snafu)

Intellivision cartridges were smaller than Atari cartridges, likely because prolonged use of the Inty’s control pad caused severe hand cramps, preventing people from opening their hands wide enough to grasp a larger cart. The cartridge has a pointed front with the game’s title on a label on the sloped surface receding from the point. There was typically no artwork on Intellivision cartridges, simply because there wasn’t enough room. In fact, there was hardly even enough real estate for the game title itself in some cases. Some Intellivision cartridges had what can best be described as a “Fill Line”, instructing you just how far to stick the cartridge into the system.  Mattel was so enamored of the Intellivision cart’s form factor that they used the same shell for their Atari 2600 versions of Intellivision titles (Known as M-Network), simply sticking on a wider base to fit the 2600’s cartridge slot. These M-Network carts even have the Fill Line.

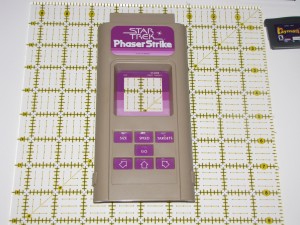

Microvision

(Pictured: Star Trek Phaser Strike)

Milton-Bradley Microvision cartridges are large, but they’re large with a purpose. You see, they’re not just the game cartridge, they’re also a face plate, controller overlay and screen overlay, all in one. They mounted on the front of the Microvision handheld system.

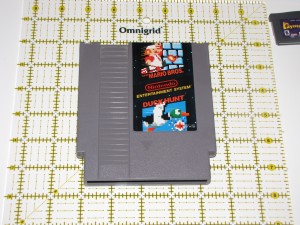

NES

(Pictured: Super Mario Bros./Duck Hunt)

The Nintendo Entertainment System was another obscure system which was released in the mid-80’s. Presumably these games are so rare because they’re absolutely freaking huge. Plus, no one really wants to play games which apparently promote cruelty to animals and pyromania. Early Nintendo-produced NES games had a fairly standarized label design, with some real game graphics ((Although slightly enhanced by exciting motion lines.)) used for the artwork and the game title set beneath it at an angle, but this quickly gave way to a free-for-all anything goes approach to label design.  And they’re freaking huge. I know I might be desecrating your memory of a classic here, but seriously. Look at them. They’re FREAKING HUGE.

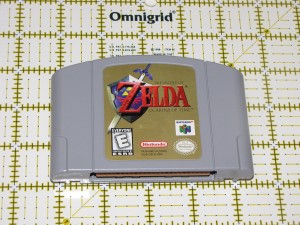

Nintendo 64

(Pictured: The Legend of Zelda Ocarina of Time)

This cartridge almost killed Nintendo. When the Nintendo 64 was released, it’s competitors were using CDs. PC games were almost exclusively released on CDs. Even third-rate lame ass systems like the Atari Jaguar had CD add-ons. CDs let you have amazing sound, extensive videos, full voice-overs, and games of unlimited size, plus, they were really really cheap. Nintendo, sensing a passing fad, decided to stick with the tried-and-true cartridge technology. The N64 sold 33 million systems, the PSX sold 125 million.

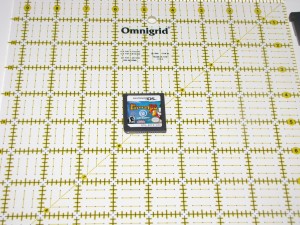

Nintendo DS

(Pictured:Â Rayman DS)

Too small.

Nokia N-Gage

(Pictured: Rayman 3)

Nokia thought they were going to take the world by storm and revolutionize the portable game market. Let’s put games on the phone, so people only have to carry one thing around. Let’s make the games 3D. Let’s get big licenses to make games for us. LET’S CRUSH THE GAME BOY! Sadly, in all of their big plans, no one stopped to add the requirement “Let’s make it usable”. In order to swap games in the original N-Gage, you had to pop the back cover of the phone off, then REMOVE THE BATTERY to reach the game card slot. Yeah, and it sucked as a phone, too. At any rate, I’m not sure if this one can even be legitimately included in this set, since N-Gage games came on a plain ordinary MMC card.

Odyssey2

(Pictured: KC’s Krazy Chase!)

The main section of an Odyssey 2 cartridge was roughly the same size as an Atari 2600 cartridge, but there was a large handle on the top of the cart. It’s unclear what prompted this design choice, but I suspect that O2 carts had the opposite problem from Game Boy and Astrocade carts, in that Odyssey2 carts would sometime refuse to leave the nice warm cartridge slot and you’d need to grab a hold of the handle and pull as hard as you can to get them out. Odyssey2 cartridges were black plastic, and had labels that were simplified monochrome renditions of the groovy black light art found on the boxes. The labels also featured a large Superman flying style “Odyssey2” logo emerging from the center of the artwork. Odyssey2 carts were all very exciting, as demonstrated by the use of an exclamation point in every single title for every game released on the system!

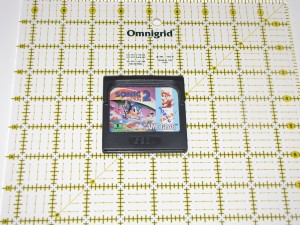

Sega Game Gear

(Pictured: Sonic the Hedgehog 2)

Like the Lynx, the Game Gear featured full color graphics and was more powerful than the Game Boy. And like the Lynx, that didn’t matter because it didn’t come with Tetris. Game Gear carts were larger than Game Boy and Lynx carts, but still small enoguh to be portable.

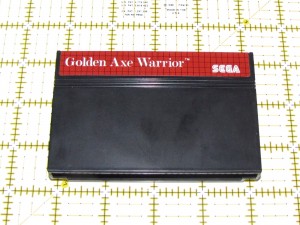

Sega Master System

(Pictured: Golden Axe Warrior)

SMS carts were smooth black plastic, with a small red label only large enough for the game title and Sega logo. But who cares about the cartridge, when the game in the picture is Golden Axe Warrior? If you have a Sega Master System, you need this game. If you don’t have a SMS, then you need to buy one, then buy this game. It’s that simple. Golden Axe Warrior is a pure rip-off of The Legend of Zelda, but it’s one of the most pitch-perfect ripoffs ever made. Change the main character to Link and the main enemy to Gannon, and you have the game that Zelda 2 should have been.

Sega Genesis

(Pictured: Sonic The Hedgehog 2)

Black and curvy. Obtrusive branding on label.

Super Nintendo

(Pictured: Super Metroid)

The Super Nintendo cartridge is one of the most complex cart designs around. The ridges and bevels of the NES cartridge weren’t enough for Nintendo, so they added screws, curves, divots, notches, and what appears to be aluminum siding. The label has a huge amount of space devoted to branding, but still manages to have room for game artwork. SNES carts aren’t quite as freaking huge as NES carts, but they’re still pretty big. Also, just like NES carts, they’re mostly empty space inside. Early Super Nintendo cartridges had a solid section across the base, which allowed a locking mechanism to fit into a hole on the front of the cartridge, but as time went on the carts evolved a way to free themselves from this capitivity, leading to the gapped cart shown above. In a rare gesture of defeat, later SNES consoles removed the locking arm entirely, thereby allowing even the early cartridges to escape.

TI-99/4A

(Pictured: Parsec)

Most cartridges are easy to stack in a pile. The TI-99 doesn’t play like that. Cartridges for that computer suddenly get fatter halfway up the cartridge, complicating any standard strategy. Your only hope is a backwards/forward alternation, but even that tends to be unstable.

Tomy Tutor

(Pictured: Traffic Jam)

Tomy Tutor cartridges ((All ten of them…)) are similar to Sega Master System carts with a different color scheme. They’re white instead of black, have white labels instead of red, and the label has a notebook paper motif instead of Sega’s graph paper styling. Almost makes up for the rubber keyboard.

TRS-80

(Pictured: Mega Bug)

Back in the history of ages past, Radio Shack did more than try to sell you cell phone contracts and RC cars. At one point, they had a fairly popular line of computers. No, they weren’t just computers. They were COLOR Computers. Special. TRS-80 carts had a large section of game art on the front, while the end label was a standard design with the Radio Shack logo, game title, and, for easy reordering, the catalog number.

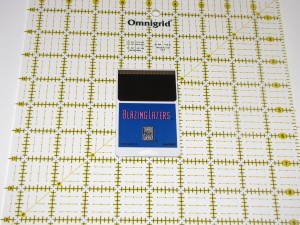

Turbo-Grafx 16

(Pictured: Blazing Lazers)

The TG-16 used cards that were pretty much the size of two credit cards stacked together. The artwork was printed directly onto the card, rather than being an applied sticker like on pretty much every other game cartridge. Most games had a large single colored patch with the game title in the TG-16 font and the TG-16 logo. Above this is a black patch, presumably housing the actual game content. When inserted into the system, the full label section remains visible.

Virtual Boy

(Pictured: Red Alarm)

Virtual Boy carts were larger than Game Boy cartridges and featured a label with a red and blue field and the stylized game title. The lack of art on the label was mitigated by the fact that most users of the Virtual Boy lost their eyesight while playing, and were therefore unable to closely examine the cartridges.

September 26, 2009 4 Comments

Electric Curiosities: Motion Sensitive Controllers

The PS3 has one that, much like the system itself, no one cares about.

The Wii built their entire reason for existing around one.

And the XBox 360 has decided that they’re completely irrelevant, and is instead trying to pass off an EyeToy rip-off as “Innovation”.

I’m talking about motion sensitive controllers, and despite what Nintendo ((And Apple, for that matter.)) might have you believe, they’re about as innovative as Project Natal. You see, the Wii isn’t the first Nintendo system to have a motion activated joystick.Â

The NES had one, called the “Game Handler”, from IMN Control. The Game Handler is basically the top half of a flight stick, without that whole pesky base that’s normally attached. The product code for this joystick is the overly optimistic “GH-001”, implying that not only were they expecting the line to produce a GH-002 and GH-003, but also a GH-100.

I have one. Unfortunately, my apparently gargantuan hands are unable to comfortably hold the controller in such a way that I can press all of the buttons without finger contortions. The main trigger and the primary thumb button are interchangable between A and B, while the two difficult to reach, yet remarkably in the way side buttons are start and select. They’re unlabeled, but that’s not a problem, because you’ll accidentally hit one of them rather frequently when you play, so you’ll soon learn which one is which.

Of course, Game Handler itself was not terribly innovative. The Atari 2600 even had a gravity controller, and I think it used real mercury switches, because it’s from back before mercury was dangerous. I’ve seen it called “Le Stick” or the “Heyco Gravity Joystick”. The joystick itself says “Heyco” on a small ring where the cord enters the base, but the plug appears to have been harvested off of a regular Atari joystick.  Although it’s decidedly phallic in appearance ((Thankfully it was released before controllers had a rumble feature…)), it’s much easier to hold this joystick than the Game Handler. Much of the simplicity is owed to the fact that it only has one button, and that button can be placed on the top, where it’s easy to press.Â

Thing of it is, this joystick is digital. That means it’s on/off. Which means you’re either tilted or not. There’s no clear indication of when you’re about to tilt far enough to trigger the switch. And it’s inconsistent. Sometimes left will move you left, sometimes it will move you left and up, and sometimes down. Just down. Not left and down. Just… Down. Down doesn’t move you down. Down moves you right. Of course. That means you play like you’re having a seizure.

[mediaplayer src=’/log/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/YarsRevengeGravity.wmv’ autoLoad=1 width=448 height=336 ]

I don’t normally suck that much at Yars’ Revenge.

Now, that much awesome simply cannot exist on its own. When you have an object this amazing, well, you just have to get two.

Next up:Â Robotron 2084.

So, in the end, it’s clear that the motion control of today’s consoles is not nearly as technologically innovative as you were led to believe. It had all been done before, nearly 30 years ago. The innovation made with this generation was that the designers decided that it would be a good idea to remove the suck from motion controllers and make something that actually worked.

September 16, 2009 1 Comment

Victory Video

I’m working on a YouTube friendly condensed version at the moment.

[Edit: Here’s the YouTube version.]

September 8, 2009 No Comments

An Even Epicker Win

21-9! Take that and dance, 30+ year old technology! I’ve got two words for you: Inyo and Face!

Video coming soon.

September 8, 2009 No Comments