Category — Electric Curiosities

Electric Curiosities: The Value of Plastic

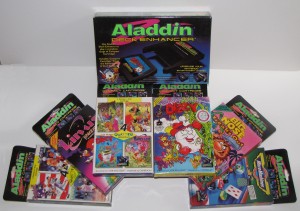

Last week, I wrote about the Aladdin Deck Enhancer. I was prompted to write about it because I had recently acquired one from a popular on-line auction site that is a primary enabler of my addiction. It was the complete set, the main unit and all six games that were released. On top of that, it was sealed. In a stroke of luck, I paid $70 for the lot. However, since it was a complete set, in very good condition and sealed, it was probably worth about $200-300. In fact, just the bare unit and all seven loose cartridges would potentially be worth $70 all by itself.

In video game collecting, as in many other types of collecting, the sealed package demands a premium. For instance, a complete copy of Super Metroid can run you $40-50, but if it’s still factory sealed, you’re looking at a minimum of $400. A used copy of Sgt. Pepper on Vinyl might sell for $10, but with an unbroken covering of the original plastic, you might have to talk to Christie’s Auction House.

Thing is, I don’t see the point.

With a quick little slice, I “lost” at least $150 on that Aladdin Deck Enhancer, and it doesn’t really bother me. ((Although, I did consider trying to find someone who had an opened copy and would be willing to trade for a sealed copy. After all, it might not be worth anything to be, but I know that someone out there might want it.)) In all honesty, what good is a bunch of games to me if I can’t play them? If it’s sealed, it might as well be a pretty box with rocks inside. While I like the container, it’s what’s contained that I really care about. I have to wonder how many other collectors out there feel the same way.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m not about to do something insane like break the seal on a copy of Chrono Trigger. Instead, I just avoid buying anything that’s still wrapped in unbroken plastic, unless the price is such that I won’t lose any sleep over it. It’s no great loss to the Video Game World that an Aladdin Deck Enhancer has been unwrapped. It’s probably still worth more than I paid, even with the plastic opened.

October 7, 2009 No Comments

Electric Curosities: Enhance your NES!

Back in the early 90’s, toward the end of the life of the NES, the company who was responsible for the Game Genie came up with another idea to make Nintendo angry. It was called the Aladdin Deck Enhancer. Reportedly designed to allow “enhanced” games on the NES by providing extra RAM and better graphics, it was called “the future of console game play” by its very own box. In reality, however, it was an ill-timed plot to sell cheap, unlicensed games for the NES.

Cartridges for the NES were fairly expensive to produce. It wasn’t just the ROM chip, a simple circuit board, and a big plastic shell, like there was in the days of the Atari. Sometimes NES games needed some extra memory, sometimes they needed a graphics coprocessor, but they always, every single one of them, needed the additional electronics to satisfy the 10NES lockout chip.

You see, Nintendo learned a lesson from the Great Crash of 83. Atari didn’t have any kind of lockout device on the Atari 2600. This allowed third party developers like Activision and Imagic to produce some of the best titles of the system without needing the permission of nor needing to pay Atari. It also allowed anyone with a ROM burner to produce mountains and mountains of unashamed garbage that masqueraded as video games. You think ET caused the Crash? No. Custer’s Revenge caused the Crash. Star Fox caused the Crash. ((Not THE Star Fox, although, interestingly enough, Star Fox for the Atari 2600 is the reason THE Star Fox had to be called “Starwing” and “Lylat Wars” in Europe. ))  Nintendo wasn’t going to let their system be killed by crappy games. The solution to this problem came in the form of the 10NES lockout.

By setting up a two-part lock electronic lock, they prevented a critical mass of lousy games from accumulating and thereby averted a full scale market implosion. ((Atari learned the same lesson. In its 7800 ProSystem console, there’s a lockout mechanism that’s so strong that it is actually against the law to export an Atari 7800 due to restrictions governing military grade cryptography. In Atari’s case, however, a second full scale market implosion was avoided, not by the lockout chip, but rather by not actually having a market that could implode.)) One part was in the console. When you put in a cartridge and turned the power on, a challenge was sent to the cartridge. If the cartridge responded properly, then you got to play the game. If the cartridge failed to respond correctly, you got a blinking power light and a flashing gray screen of death. And the only place to get the chip that acted like the key to the lock was Nintendo. They patented and copyrighted the design, so they’d sue you no matter what you tried to do to circumvent the lockout. But, Nintendo also recognized that the key to a successful console was third party support. Game publishers were welcome to make games for the NES, as long as they abided by all sorts of requirements and rules (Including censorship), and, on top of that, pay for the privilege of getting the chip for the cartridge and the “Nintendo Seal of Quality” on the box.

The program was successful. Because of it, Nintendo avoided a flood of terrible and worthless games. Sure, there were games that sucked, but for the most part, anything that had the Nintendo Seal of Quality was at least half-way decent.  Even crap-buckets like Total Recall or Super Pitfall were miles above the uninspired and derivative silicon wastelands that plagued the Atari 2600 in 1983.   The lockout chip also made piracy of NES carts more difficult. Without the 10NES key chip, a game wouldn’t play, and Nintendo wasn’t about to hand out those chips to pirates.

Of course, the flip side should be obvious. Because Nintendo controlled the chip that was the key to the system, Nintendo controlled every game that was allowed to play on it. Want to put out a game with blood in it? Nope. Want a game with strong religious themes or symbols? Ain’t gonna happen. Adult content or mature themes? Uh-uh. Want to release the same game for the NES and for Sega? Not for another couple of years. Want to put out more than a handful of games a year? Fat chance.

Don’t want to pay the licensing fee to Nintendo…?

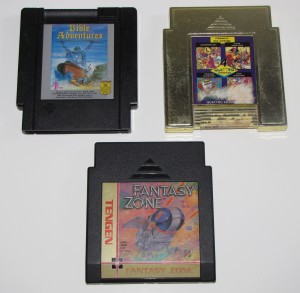

Whenever there is a technology that will prevent someone from making money, that someone will find a way to defeat that technology, thereby allowing money to be made. That is exactly what happened with the 10NES lockout chip. Some people created pass-through carts, which looked like a Game Genie and required you to plug in a licensed NES cartridge in order to play. It then used the real 10NES chip in the licensed cartridge to unlock the NES, which then loaded the unlicensed game in the passthrough. Other companies thought that was too tacky looking and instead decided to simply fry the 10NES chip in the NES system by sending it a voltage spike. However, the truly dedicated ones reverse engineered the 10NES chip from the specifications in documents obtained under false pretenses from the US Patent Office. The corporation who was responsible for this awesome act of technological trickery? Atari. The Atari who had been nearly destroyed by unlicensed games had decided to create its own unlicensed NES games under the Tengen brand, largely to get around Nintendo’s licensing fees and severe non-compete restrictions. ((And, of course, they got sued… Although some may claim that the lawsuit was less about protecting their technology than protecting their reputation, as the lawsuit focused on the Tengen version of Tetris, generally considered superior to the Nintendo version. (Much the same way that Atari had sued Magnavox for the superior K.C. Munchkin infringing on the less-than-stellar 2600 Pac-Man…) ))

Unlicensed NES Cartridges: Bible Adventures (Wisdom Tree), Quattro Adventure (Camerica), Fantasy Zone (Tengen)

Most manufacturers of unlicensed NES games ended up following in Atari/Tengen’s shoes and created 10NES knock-off chips. However, those chips raised the cost of producing a cartridge and cut into the profit margin. Which brings us back to the Aladdin Deck Enhancer that I was talking about before I went off on that long-winded tangent of a history lesson. You see, there was nothing about the Aladdin Deck Enhancer that was really an enhancement at all.  It actually wasn’t about the extra memory, it actually wasn’t about the graphics coprocessor. It was about the knock-off 10NES chip. The plan behind the Aladdin Deck Enhancer was that they’d sell the base cartridge, which contained the lockout chip and some other chips, then sell the games that plugged into the base separately. As many games as you wanted, but only one lockout chip. The games, since they wouldn’t need to include the extra electronics, would be cheaper to produce and therefore cheaper to sell. On top of that, why not license other games for use with the Aladdin Deck Enhancer? Certainly there are other companies or game developers itching to get their games on the NES without having to deal with the Iron Fist of the Big N. It’s like a license to print money!

Or rather, in 1988, it would have been a license to print money. But the Aladdin Deck Enhancer came out in 1993, firmly in the period of 16-bit domination. If people wanted enhanced graphics and bigger games, they didn’t buy games on some convoluted half cartridge that required some bizarre mutant shell for them to work. No, they went out and bought a Super Nintendo. The company which distributed the Aladdin Deck Enhancer was ruined and folded a few months later.

The game “Dizzy The Adventurer” was included as a pack-in cartridge. The other six cartridges released were The Fantastic Adventures of Dizzy, Quattro Adventure (including Boomerang Kid, Super Robin Hood, Linus Spacehead, and Treasure Island Dizzy ((It’s obvious that Codemasters felt that Dizzy would be their killer app, with three Dizzy games available for the unit and another one promised on the box. Although apparently big in the UK, sadly, the failure of unit meant that Prince Dizzy of the Yolk Folk would remain obscure in the US…)) ), Big Nose Freaks Out, Micro Machines, Quattro Sports (including Baseball Pros, Soccer Simulator, Pro Tennis, and BMX Simulator), and Linus Spacehead’s Cosmic Crusade. ((If you’re ever in need of a Commodore 64 flashback, you should give Dizzy or the games on Quattro Adventure a spin. Not that you ever actually played those games on a C64, but they’ll certainly remind you of one.)) 11 other games were promised on the box, and while none of those were released as Deck Enhancer carts, most were later (or had already been) released as standalone unlicensed NES carts. While not crowning pinnacles of gaming glory, the Aladdin games aren’t complete abuses of the physical properties of silicon.  It’s likely that some of the games would have easily been qualified for the “Nintendo Seal of Approval”, had they wished to go legit. ((And if they hadn’t been made by the same people who made the Game Genie…))

October 3, 2009 2 Comments

Electric Curiosities: The Lost Art of Cartridge Design

These days, with the exception of the Nintendo DS, video games come on boring shiny discs that look pretty much exactly the same as every other game for every other competitor’s system. You can’t tell the difference between the games for two consoles by feel alone.

It was not always like this. Deep in the mists of time, video games all came in chunks of plastic called “Cartridges”. By look and feel, you could distinguish one system’s games from another’s. Sometimes cartridges for a system were plain and rectangular, sometimes they were embellished with features like handles, and sometimes they were yellow… Bright yellow. This post explores the cartridges for a number of different systems, some of which may be familiar to you, and some of which will hopefully strike you as freakish and bizarre.

First off, the full gallery, for size comparison. For fun, I’d recommend trying to see how many of these cartridges you can identify without zooming in all the way and reading their logos.

If you don’t recognize at least three, you’re probably not going to find the rest of this post very interesting. And if you can name all of them, then feel free to start naming cartridge-based systems that aren’t represented here. There are still a few systems that I haven’t raided eBay for yet…

Anyway, without further babbling, the carts:

Atari 400

(Pictured: Centipede)

The Atari 400 computer had a small (by Atari standards) cartridge with a plain text brown label. The cart contacts were protected by a sliding door, which was partially exposed, unlike the doors on 2600 and 5200 carts. The Atari 800 had two cartridge slots (because one is never enough), but the slots were not equivalent, forcing Atari 400/800 games to have a marking on the top of the cart telling you to insert it into the left or the right cartridge port. However, since people didn’t buy the Atari 800, not many cartridges were made for the exclusive right port, leaving it lonely and depressed. ((It later found love in the form of the similarly ignored NES expansion port.))

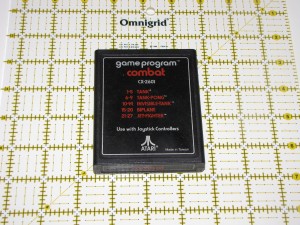

Atari 2600

(Pictured: Combat)

According to what trusted sellers on eBay have told me, this is Combat for the Atari 2600, which is apparently EXTREMELY RARE (LQQK!). I had never heard of this game or this system before, so I don’t have much information on it to share.

Atari 5200

(Pictured: Robotron 2084)

After their apparent disastrous failure with the Atari 2600, Atari bounced back and produced the Atari 5200, which, as the name implies, was twice as good as the 2600. 5200 carts were the largest Atari carts, with the height of a 2600 cartridge, but the width of a SNES cartridge. Typical 5200 carts were silver labels, with an image on the label and blue Atari branding. Unlike the multiple rebrands of Atari 2600 cartridges, the 5200 did not survive long enough to change this basic design.

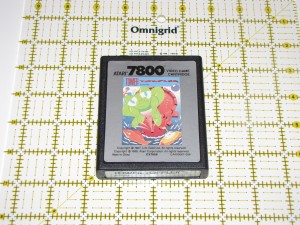

Atari 7800

(Pictured: Tower Toppler) ((Also known as Nebulus or Castelian))

During the rise of the NES, Atari released the 7800 ProSystem. Learning from some of the mistakes they made with the 5200, the 7800 had 2600 compatibility, which lead to the 7800 using a size and shape identical to the 2600 for its cartridges. 7800 carts mostly had a silver border and plain text end label, with game art in the middle of the main label.

Atari Jaguar

(Pictured: Iron Soldier)

The last gasp of the once powerful Atari, the Jaguar came out right at the transition between 2D and 3D and would have had more success had most of its games not completely sucked. (I’m looking at you, Checkered Flag. And Club Drive.) The cartridges used the extremely popular 2.75 x 4 form factor (Similar to the size used by the Genesis, SMS, Famicom, N64, TRS-80, TI-99, and Tomy Tutor), but for some inexplicable reason, had a tube shaped handle on the top.

Atari Lynx

(Pictured: Scrapyard Dog)

Lynx games are some of the flattest in this set, about two credit cards thick. The contacts are exposed directly beneath the label. Most Lynx games had a curved lip at the top edge, allowing you to pull the game out of the system after it’s inserted. The Lynx is one of the few systems in this set where you can’t see what game is in the system after you’ve put the cart in, as the label faces the back of the system, instead of outward like on the Game Boy.

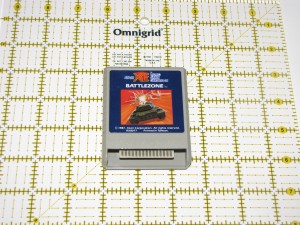

Atari XE

(Pictured: Battlezone)

The Atari XE Game System was Atari’s competitor to the Atari 7800. The two systems fought each other valiantly and both were slain in the process. The XE was compatible with Atari 400/800 series games, so XE carts were the same size and shape. The color was changed because by the late 80’s, people had realized that the early 80’s were ugly. The label was updated to include game art. And finally, the bizarre half-exposed dust door on the 400’s carts was removed for the XE.

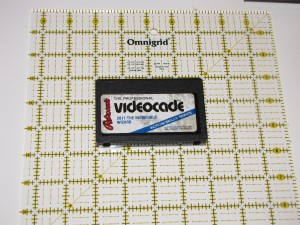

Bally Videocade

(Pictured: The Incredible Wizard)

Bally Astrocade/Videocade/Professional Arcade ((No one seems to actually know what this thing was called, not even the system itself.)) had cartridges that wanted to be cassette tapes. While they didn’t have winding spools or magnetic tape, they did have what appears to be write-protect tabs that were punched out. These holes were used to hold the cartridge in place after you inserted it, because Astrovision Videocade ((or whatever)) cartridges possessed limited intelligence and were known to try to escape when you turned the system on.

ColecoVision

(Pictured: Donkey Kong)

The ColecoVision knew a good thing when it saw it. Why try to come up with your own cartridge design when you can steal the one that was Atari was using?  Coleco carts are the same size and shape as Atari 2600 cartridges, but had controller overlay slots in the back and the label was reversed so that you’d see it the right way up when it was in the system. Oh, and there were little ridgey things at the top, and the case was slightly beveled to prevent you from trying to jam a Coleco cart in an Atari or an Atari cart into a ColecoVision. This cartridge camouflage is especially useful now, as less savvy eBay sellers can’t tell the difference between an Atari 2600 cartridge and a generally more valuable ColecoVision cartridge, allowing someone who can tell the difference to take advantage of them. Unfortunately, the label design for a Coleco game kinda sucks, giving the ColecoVision name more prominence than the cartridge title, and limiting the custom artwork to the title itself. ((And when they were selling the Adam computer, the corporate labeling read “ColecoVision & ADAM”, making it even larger and even more obnoxious.))

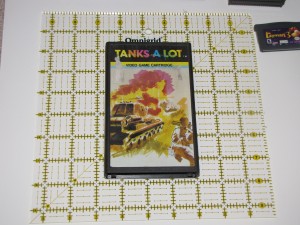

Emerson Arcadia 2001

(Pictured: Tanks A Lot)

The Emerson Arcadia 2001 wasn’t satisfied with the 3×4 cartridge that the Atari and Coleco had. Oh no, they had to push it to the max. As a result, the Arcadia carts are 6 FULL INCHES of rainbow-titled watercolor AWESOME. And why stop there? Why not put a label on the BACK side of the cartridge, too?

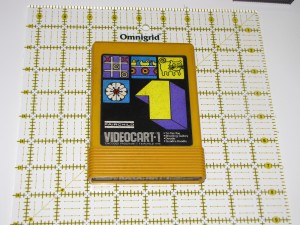

Fairchild Channel F

(Pictured: Videocart 1: Tic-Tac-Toe/Shooting Gallery/Doodle/QuadraDoodle)

They’re yellow. They’re big. And they’ve got giant psychedelic numbers on them.

Nintendo Game Boy

(Pictured: Kirby’s Dream Land)

Game Boy cartridges are about the smallest a cartridge can get without feeling too small. It’s large enough that you can’t eat it and won’t permanently lose it in the seat cushions, but small enough to take large quantities with you wherever you go. It’s got a big spot for label art that isn’t invaded by branding, since the branding is built into the cart itself. These carts must have evolved from stray Bally carts, as they also have a notch for a locking device to prevent their escape. It’s also one of the few carts that tells you how to put it in the system, with a large arrow in the plastic and the words “THIS SIDE OUT” on the label.

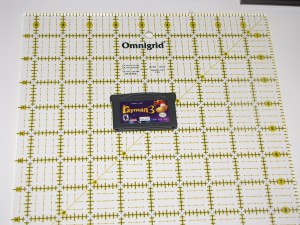

Game Boy Advance

(Pictured: Rayman 3)

The GBA cartridge was about half the height of a Game Boy cart, leaving less room for artwork on the label. The system branding is still on the plastic and the insertion arrow is still there, but the label no longer tells you which direction faces out, leading to mass customer confusion.

Game Boy Color

(Pictured: Blaster Master Enemy Below and The Legend of Zelda Oracle of Seasons)

The Game Boy Color cheats in its quest to gain attention by having two types of cartridge that I have to comment on. There’s the Black Mutant Hybrid cartridges, which are identical to standard Game Boy carts, only black. These mutated black cartridges could be played on an ordinary Game Boy, but also contained Game Boy Colorized versions of the games. Then there’s the similarly sized clear carts, which are strictly for the Game Boy Color. The system branding region that had been indented on regular Game Boy carts was inverted into a bubble on the clear carts. Additionally, by the release of the GBC, the clear carts had been sufficiently tamed and no longer attempted to flee when they were played, so there was no need for a locking mechanism on the system, which means that they do not have a notch in one of the corners.

Intellivision

(Pictured: Snafu)

Intellivision cartridges were smaller than Atari cartridges, likely because prolonged use of the Inty’s control pad caused severe hand cramps, preventing people from opening their hands wide enough to grasp a larger cart. The cartridge has a pointed front with the game’s title on a label on the sloped surface receding from the point. There was typically no artwork on Intellivision cartridges, simply because there wasn’t enough room. In fact, there was hardly even enough real estate for the game title itself in some cases. Some Intellivision cartridges had what can best be described as a “Fill Line”, instructing you just how far to stick the cartridge into the system.  Mattel was so enamored of the Intellivision cart’s form factor that they used the same shell for their Atari 2600 versions of Intellivision titles (Known as M-Network), simply sticking on a wider base to fit the 2600’s cartridge slot. These M-Network carts even have the Fill Line.

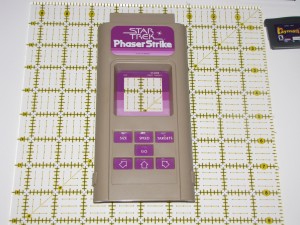

Microvision

(Pictured: Star Trek Phaser Strike)

Milton-Bradley Microvision cartridges are large, but they’re large with a purpose. You see, they’re not just the game cartridge, they’re also a face plate, controller overlay and screen overlay, all in one. They mounted on the front of the Microvision handheld system.

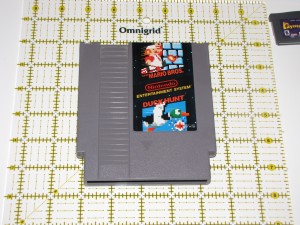

NES

(Pictured: Super Mario Bros./Duck Hunt)

The Nintendo Entertainment System was another obscure system which was released in the mid-80’s. Presumably these games are so rare because they’re absolutely freaking huge. Plus, no one really wants to play games which apparently promote cruelty to animals and pyromania. Early Nintendo-produced NES games had a fairly standarized label design, with some real game graphics ((Although slightly enhanced by exciting motion lines.)) used for the artwork and the game title set beneath it at an angle, but this quickly gave way to a free-for-all anything goes approach to label design.  And they’re freaking huge. I know I might be desecrating your memory of a classic here, but seriously. Look at them. They’re FREAKING HUGE.

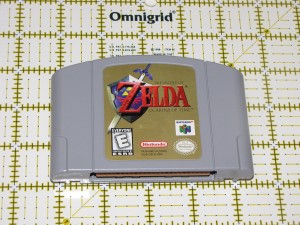

Nintendo 64

(Pictured: The Legend of Zelda Ocarina of Time)

This cartridge almost killed Nintendo. When the Nintendo 64 was released, it’s competitors were using CDs. PC games were almost exclusively released on CDs. Even third-rate lame ass systems like the Atari Jaguar had CD add-ons. CDs let you have amazing sound, extensive videos, full voice-overs, and games of unlimited size, plus, they were really really cheap. Nintendo, sensing a passing fad, decided to stick with the tried-and-true cartridge technology. The N64 sold 33 million systems, the PSX sold 125 million.

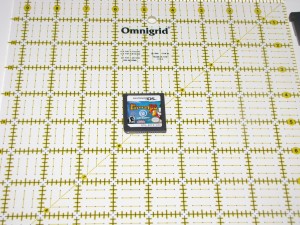

Nintendo DS

(Pictured:Â Rayman DS)

Too small.

Nokia N-Gage

(Pictured: Rayman 3)

Nokia thought they were going to take the world by storm and revolutionize the portable game market. Let’s put games on the phone, so people only have to carry one thing around. Let’s make the games 3D. Let’s get big licenses to make games for us. LET’S CRUSH THE GAME BOY! Sadly, in all of their big plans, no one stopped to add the requirement “Let’s make it usable”. In order to swap games in the original N-Gage, you had to pop the back cover of the phone off, then REMOVE THE BATTERY to reach the game card slot. Yeah, and it sucked as a phone, too. At any rate, I’m not sure if this one can even be legitimately included in this set, since N-Gage games came on a plain ordinary MMC card.

Odyssey2

(Pictured: KC’s Krazy Chase!)

The main section of an Odyssey 2 cartridge was roughly the same size as an Atari 2600 cartridge, but there was a large handle on the top of the cart. It’s unclear what prompted this design choice, but I suspect that O2 carts had the opposite problem from Game Boy and Astrocade carts, in that Odyssey2 carts would sometime refuse to leave the nice warm cartridge slot and you’d need to grab a hold of the handle and pull as hard as you can to get them out. Odyssey2 cartridges were black plastic, and had labels that were simplified monochrome renditions of the groovy black light art found on the boxes. The labels also featured a large Superman flying style “Odyssey2” logo emerging from the center of the artwork. Odyssey2 carts were all very exciting, as demonstrated by the use of an exclamation point in every single title for every game released on the system!

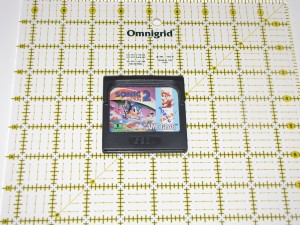

Sega Game Gear

(Pictured: Sonic the Hedgehog 2)

Like the Lynx, the Game Gear featured full color graphics and was more powerful than the Game Boy. And like the Lynx, that didn’t matter because it didn’t come with Tetris. Game Gear carts were larger than Game Boy and Lynx carts, but still small enoguh to be portable.

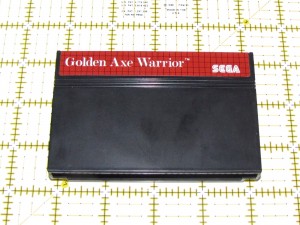

Sega Master System

(Pictured: Golden Axe Warrior)

SMS carts were smooth black plastic, with a small red label only large enough for the game title and Sega logo. But who cares about the cartridge, when the game in the picture is Golden Axe Warrior? If you have a Sega Master System, you need this game. If you don’t have a SMS, then you need to buy one, then buy this game. It’s that simple. Golden Axe Warrior is a pure rip-off of The Legend of Zelda, but it’s one of the most pitch-perfect ripoffs ever made. Change the main character to Link and the main enemy to Gannon, and you have the game that Zelda 2 should have been.

Sega Genesis

(Pictured: Sonic The Hedgehog 2)

Black and curvy. Obtrusive branding on label.

Super Nintendo

(Pictured: Super Metroid)

The Super Nintendo cartridge is one of the most complex cart designs around. The ridges and bevels of the NES cartridge weren’t enough for Nintendo, so they added screws, curves, divots, notches, and what appears to be aluminum siding. The label has a huge amount of space devoted to branding, but still manages to have room for game artwork. SNES carts aren’t quite as freaking huge as NES carts, but they’re still pretty big. Also, just like NES carts, they’re mostly empty space inside. Early Super Nintendo cartridges had a solid section across the base, which allowed a locking mechanism to fit into a hole on the front of the cartridge, but as time went on the carts evolved a way to free themselves from this capitivity, leading to the gapped cart shown above. In a rare gesture of defeat, later SNES consoles removed the locking arm entirely, thereby allowing even the early cartridges to escape.

TI-99/4A

(Pictured: Parsec)

Most cartridges are easy to stack in a pile. The TI-99 doesn’t play like that. Cartridges for that computer suddenly get fatter halfway up the cartridge, complicating any standard strategy. Your only hope is a backwards/forward alternation, but even that tends to be unstable.

Tomy Tutor

(Pictured: Traffic Jam)

Tomy Tutor cartridges ((All ten of them…)) are similar to Sega Master System carts with a different color scheme. They’re white instead of black, have white labels instead of red, and the label has a notebook paper motif instead of Sega’s graph paper styling. Almost makes up for the rubber keyboard.

TRS-80

(Pictured: Mega Bug)

Back in the history of ages past, Radio Shack did more than try to sell you cell phone contracts and RC cars. At one point, they had a fairly popular line of computers. No, they weren’t just computers. They were COLOR Computers. Special. TRS-80 carts had a large section of game art on the front, while the end label was a standard design with the Radio Shack logo, game title, and, for easy reordering, the catalog number.

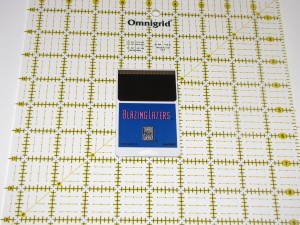

Turbo-Grafx 16

(Pictured: Blazing Lazers)

The TG-16 used cards that were pretty much the size of two credit cards stacked together. The artwork was printed directly onto the card, rather than being an applied sticker like on pretty much every other game cartridge. Most games had a large single colored patch with the game title in the TG-16 font and the TG-16 logo. Above this is a black patch, presumably housing the actual game content. When inserted into the system, the full label section remains visible.

Virtual Boy

(Pictured: Red Alarm)

Virtual Boy carts were larger than Game Boy cartridges and featured a label with a red and blue field and the stylized game title. The lack of art on the label was mitigated by the fact that most users of the Virtual Boy lost their eyesight while playing, and were therefore unable to closely examine the cartridges.

September 26, 2009 4 Comments

Electric Curiosities: Motion Sensitive Controllers

The PS3 has one that, much like the system itself, no one cares about.

The Wii built their entire reason for existing around one.

And the XBox 360 has decided that they’re completely irrelevant, and is instead trying to pass off an EyeToy rip-off as “Innovation”.

I’m talking about motion sensitive controllers, and despite what Nintendo ((And Apple, for that matter.)) might have you believe, they’re about as innovative as Project Natal. You see, the Wii isn’t the first Nintendo system to have a motion activated joystick.Â

The NES had one, called the “Game Handler”, from IMN Control. The Game Handler is basically the top half of a flight stick, without that whole pesky base that’s normally attached. The product code for this joystick is the overly optimistic “GH-001”, implying that not only were they expecting the line to produce a GH-002 and GH-003, but also a GH-100.

I have one. Unfortunately, my apparently gargantuan hands are unable to comfortably hold the controller in such a way that I can press all of the buttons without finger contortions. The main trigger and the primary thumb button are interchangable between A and B, while the two difficult to reach, yet remarkably in the way side buttons are start and select. They’re unlabeled, but that’s not a problem, because you’ll accidentally hit one of them rather frequently when you play, so you’ll soon learn which one is which.

Of course, Game Handler itself was not terribly innovative. The Atari 2600 even had a gravity controller, and I think it used real mercury switches, because it’s from back before mercury was dangerous. I’ve seen it called “Le Stick” or the “Heyco Gravity Joystick”. The joystick itself says “Heyco” on a small ring where the cord enters the base, but the plug appears to have been harvested off of a regular Atari joystick.  Although it’s decidedly phallic in appearance ((Thankfully it was released before controllers had a rumble feature…)), it’s much easier to hold this joystick than the Game Handler. Much of the simplicity is owed to the fact that it only has one button, and that button can be placed on the top, where it’s easy to press.Â

Thing of it is, this joystick is digital. That means it’s on/off. Which means you’re either tilted or not. There’s no clear indication of when you’re about to tilt far enough to trigger the switch. And it’s inconsistent. Sometimes left will move you left, sometimes it will move you left and up, and sometimes down. Just down. Not left and down. Just… Down. Down doesn’t move you down. Down moves you right. Of course. That means you play like you’re having a seizure.

[mediaplayer src=’/log/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/YarsRevengeGravity.wmv’ autoLoad=1 width=448 height=336 ]

I don’t normally suck that much at Yars’ Revenge.

Now, that much awesome simply cannot exist on its own. When you have an object this amazing, well, you just have to get two.

Next up:Â Robotron 2084.

So, in the end, it’s clear that the motion control of today’s consoles is not nearly as technologically innovative as you were led to believe. It had all been done before, nearly 30 years ago. The innovation made with this generation was that the designers decided that it would be a good idea to remove the suck from motion controllers and make something that actually worked.

September 16, 2009 1 Comment