Posts from — May 2012

Inside the B Reactor

At the height of WWII, the US government took over a stretch of desert along the Columbia River in southern Washington. They kicked out the residents of Hanford and White Bluffs, then moved in thousands of builders, engineers, and scientists, and embarked on one of the largest construction projects in history. Practically overnight, Richland became one of the largest cities in the state.

And almost no one knew what they were doing there.

Everything was secret. You didn’t talk about what you did and you didn’t speculate about others. Your phones were tapped and your mail was read.  You knew that your work was vital for the war effort in some way, but you had no idea what you were doing. Until, that is, you opened up the newspaper on August 6th, 1945, and saw the headline:

The desolate patch of sand and scrub brush had been home to the plutonium production facilities for the Manhattan Project, the secret project to build atomic bombs.

The first full scale reactor built on the site was the B Reactor, overseen by Enrico Fermi. Formerly one of the most secret facilities in the entire world, the B Reactor is now open for public tours.

The tour starts at a small business park north of Richland.

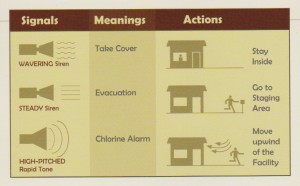

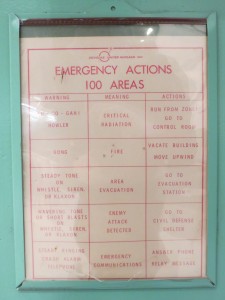

You sign in and are given a Hanford Visitor Guide. The guide, among other things, talks about the dangers of beryllium, has a convenient graphic about how to react to different types of alarms, has about six pages of information on radiation safety (out of a 20 page pamphlet), and starts off by saying “We expect that every individual will go home in the same condition that brought them to the Hanford Site.”

It’s somewhere around this point that you realize that when normal people go on vacation, they typically don’t go someplace where the brochure tells them to  “Move upwind of the facility”.

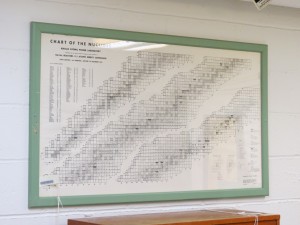

You then head into the waiting room, where a video is playing about the history and cleanup efforts of the Hanford site. Around the walls are old photos of life in the Hanford area before, after, and during the war, as well as miscellaneous sciencey artifacts. There’s also a slightly creepy pair of scale mannequins of Enrico Fermi and Leona Libby, who were scientists on the project.

From there, you’re loaded onto the bus for the 40 minute ride out to the reactor.

The trip passes through unremarkable desert. Along the way, a guide will tell you of the history of Hanford. (Our guide was a retired Hanford engineer.) Occasionally, in the distance, you catch a glimpse of some large, mysterious buildings.

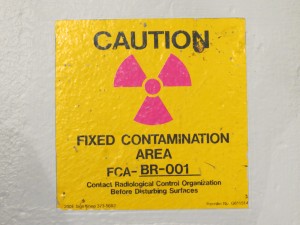

As you approach the Vernita Bridge across the Columbia River, you turn off the main road, and pass through a gate and into the Hanford site. A short time later, you pass a large yellow and magenta sign letting you know that you are entering a radiologically controlled area.

Your destination is a blocky concrete building surrounded by a chain link fence topped with barbed wire.

They unload the bus and collect everyone inside a sterile industrial hallway.  Pipes and conduits line the walls and ceilings.

Above the doorway at the far end is a sign with flashing red lights.

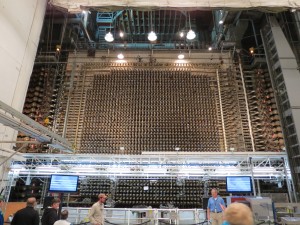

Through the door is the reactor chamber. From the hallway, it looks a bit like a school gymnasium. An American flag hangs along one side of the large open room. As you enter, you’re unsure of what you’ll be able to see. Nuclear reactors are always hidden behind ten foot thick concrete, right? There might be a super-thick lead glass window into the core. Maybe there’s one of those hot-box things with the remote controlled arms. Whatever is there, it’s probably hidden behind so much protective shielding that there’s not going to be anything to see really, right?

Then you enter the room and turn to your left. What you see looks absolutely nothing like a nuclear reactor and absolutely everything like the crazy product of a top secret government science experiment. If someone told you that it was a device that could open an interdimensional portal for travel to another planet, you would believe them. There’s no shielding, no leaded glass, no thick concrete walls, just this:

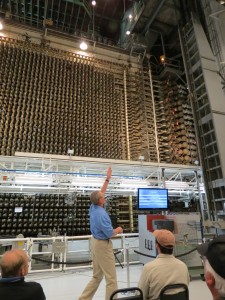

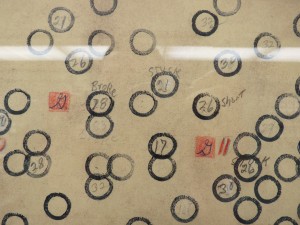

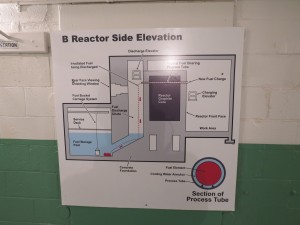

No picture can do justice to the scale. This wall of valves and pipes and caps is something like five stories high and 50 feet wide. An elevator platform stretches across the front. There are over 2000 individual process tubes on the reactor face, each one tagged and numbered. Lights flash at the corners. From holes in the ceiling above the reactor hang cables supporting something out of view. The reactor core is made up of thousands upon thousands of graphite blocks, stacked up like oversized Jenga blocks, without nails, pins, mortar, or anything else to keep them in place. This becomes even more impressive when you consider that the process tubes and holes for the control rods were pre-drilled in these blocks and had to be perfectly aligned to allow the fuel rods and control rods to pass through the core.

After about a half hour presentation, the group is split in two and taken on a tour of the rest of the site. The highlight is the control room, with its walls full of knobs and dials and gauges and readouts, but not a single computer screen.

The valve pit is full of pipes and pumps which pulled water in from the Columbia River and pushed it through the reactor to cool it down. The water was heated from the cold river temperature to almost boiling as it passed through the core.

The electrical room:

The “Hear-Here!” Telephone Booth:

The accumulator room. These large metal drums were filled with rocks and lifted into the air. In the event of a power failure the weight of the rocks pushing down would provide enough pressure in a hydraulic system to insert the control rods and stop the reaction.

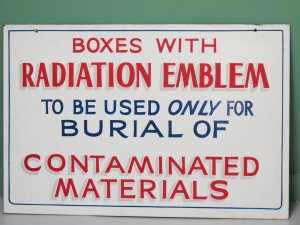

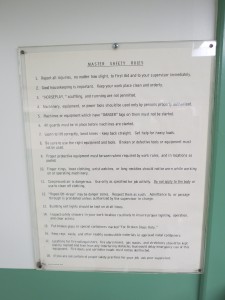

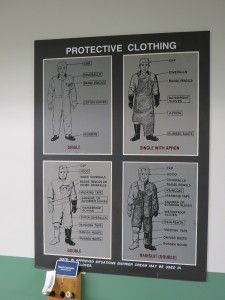

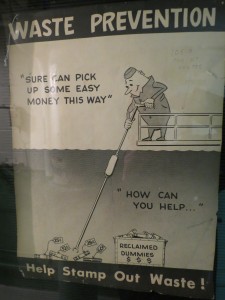

Warning signs room. These signs were originally located around the site, but have now been collected into this one room, along with some safety equipment.

This is one of the graphite blocks that makes up the core.

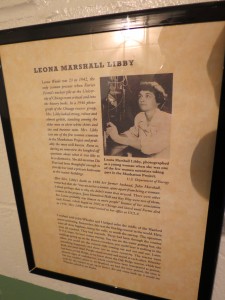

Leona Libby was one of the physicists working with Enrico Fermi. She helped solve the “Xenon posioning” problem which was causing the reactor to shutdown shortly after it was started up.

Also, they had to carve out a stall from the bathroom to make a women’s restroom specifically for her.

Off of the control room were offices for some of the staff. One of these belonged to Enrico Fermi.

Behind the reactor core is the fuel storage room. This room sits above a pool where the fuel rods ended up after being thrown out of the back side of the reactor. The rods were collected from here and shipped off to another facility on the Hanford site for plutonium extraction. The pool room is only visible through a window, and the discharge area of the reactor (Which would have been the most radioactive part of the plant, when the reactor was operating) is not visible at all.

Operations at the B Reactor did not cease after WWII. It continued to operate until 1968. As a result, not everything from the reactor is as it was during the days of the Manhattan Project. It’s difficult to tell what’s original and what was added later, unless, of course, it has a date on it.

After about three hours on site, everyone’s gathered back up and put on the bus back to Richland.

One thing I heard from some of the other people on the tour over and over, was how impressed they were that the scientists and engineers were able to build all of this from scratch, without computers, figuring it all out as they went. That wasn’t what was truly impressive to me. What I found the most impressive was the sense that somewhere, right now, there’s a group of people tucked away in a secret lab somewhere, doing pretty much exactly the same thing.

May 5, 2012 No Comments